The Incense Room

A Journey Through Springtime Along the River & The Incense Room

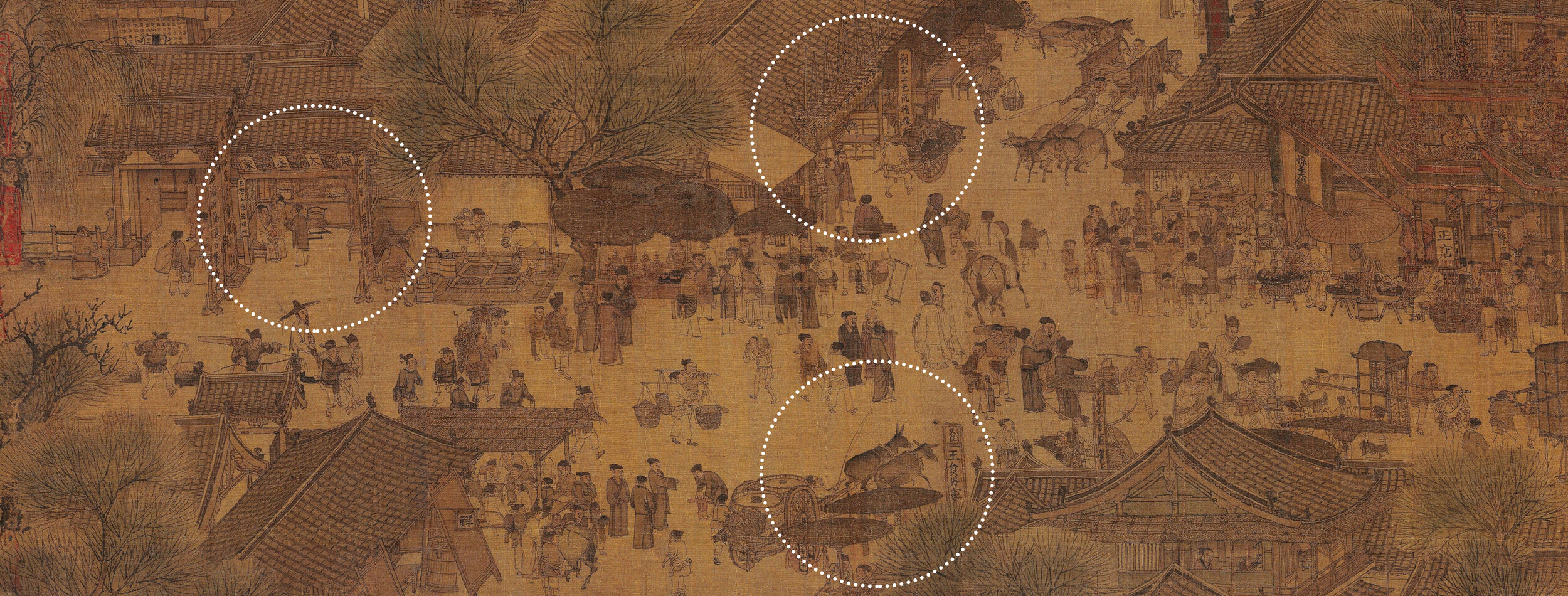

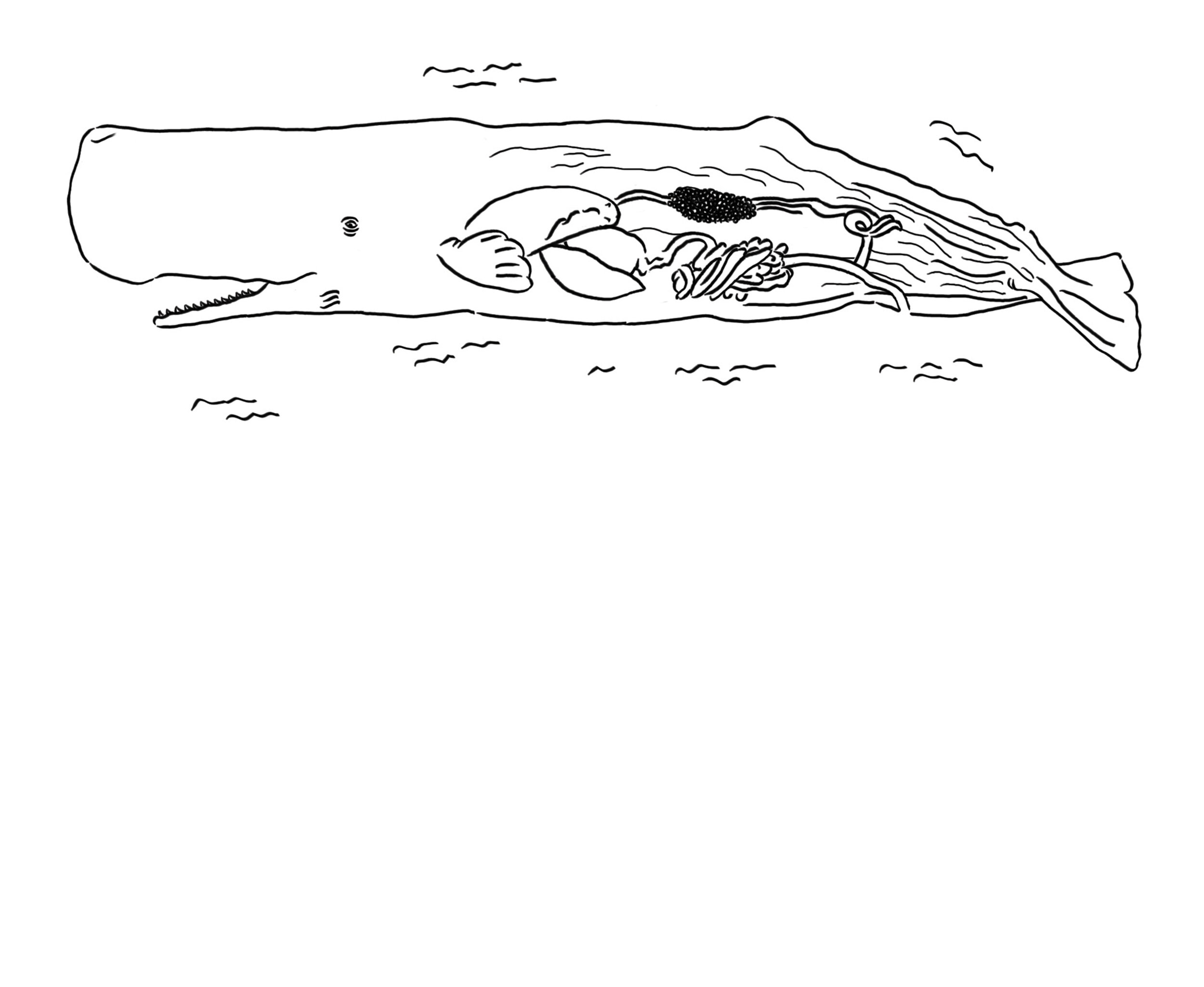

Arguably the most well-known painting in Chinese history, the Qingming Shanghe tu depicts a scene of Song dynasty life in the historical city of Bianfeng (today’s Kaifeng). The scroll is only about twenty-five centimeters high but is more than five and a half meters long. A cross-section through the city unfolds through various daily ctivities along its length—leaving behind an archive of information about architecture, technology, material culture, social relations, and globalization that is now over one-thousand years old. For scholars and critics it remains a cipher and as a mirror its various interpretations often reveal more about the political entanglements and values at play at the moment of interpretation than about the original scroll. The painting has also been copied by the court artists of various dynasties, reimagined to reflect the material culture and technologies of those times. Today the original scroll is held in the Forbidden City Palace Museum in Beijing and is rarely displayed to the public, and furthermore has only left the mainland twice for exhibit in its history. Gugong (故宫), the Palace Museum, and China’s Phoenix Television collaborated to host the exhibition held in Hong Kong in the summer of 2019. The exhibition was centered around a digital recreation of the scroll animated and rendered by the artists at Phoenix over the course of three years. Accompanying the animated scroll was an exhibition diving into historical research of the Song dynasty—anchored by various elements and details found in the painting. Inspired by the Song concept of spaces built for the appreciation of incense ritual, ATLAS’ contribution to the exhibition was an exploration of Song incense culture that resulted in an interactive multi-media installation and body of research on the intricacies of scent.

Section of the scroll.

“In the painstaking minutiae of its details, the painting “Springtime Along the River“ (清明上河圖 ) embodies progressive values of urban and civic nature: diversity is here celebrated both in the monumentality of its environmental scapes - natural, man-made, haphazard or ‘designed’ — as well as in the social and occupational multiplicity which characterized the unparalleled prosperity of the Chinese empire during medieval times. This vision of sociability and accessibility is the timeless and universal feature that from antiquity to contemporary times has never ceased to inspire great thinkers — it is the image of an “open city“.

Due to the specific form of consumption that characterizes hand-scroll painting (that is sequential reading), “Springtime Along River“ literally embodies a voyage in both time and space inside the day of a bustling urban centre. The temporal narrative begins at dawn in a tranquil rural scenario, and takes the observer through the city‘s suburbs among its markets and busy river banks, until revealing the frenzied life of the inner quarters of the walled city in the afternoon hours.”

-from the curator, Beatrice Leanza

“A highlight of the show are ten installations commissioned especially for this exhibition to ten of the most talented designers working in China today and specialized in a variety of design languages, from architecture to graphic and info design, craft research, product and textiles as well as visual communication. The result of months of research, each of these works focuses on a particular aspect of Song history to offer audiences ways to experience more broadly the importance and relation of said subjects to contemporary urban life and visual culture.”

-from the curator, Beatrice Leanza

The Incense Room

Scent communicates with an immediacy that goes directly to the deepest levels of our being—feelings such as fear, hunger, desire, calm, euphoria, can all be evoked through smell. Constructed fragrances therefore can be understood as an artistic means of manipulating the sensory realm to create a series of effects. The Chinese word “Xiang,” loosely translates to “aromatic,” but also can mean fragrance, scent, spice, or incense. Xiang implies something that transcends its simple physical state to merge with one’s being and create a spatio-sensory connection in its presence. Aromatics create a space, a sense of time, and narrative—yet remain elusive. In the Song Dynasty the burning of incense was a ritual that could mark social occasions, spiritual encounters, or even help keep a precise measure of time. While perfume was a distinctly western custom, for the people of Song times the practice of blending incense and burning it, wearing incense as sachets on the body, eating or drinking aromatics, or inhabiting rooms or pavilions dedicated solely to incense practice, were all means of mediating the body’s experience and inhabiting a world rendered by fragrance.

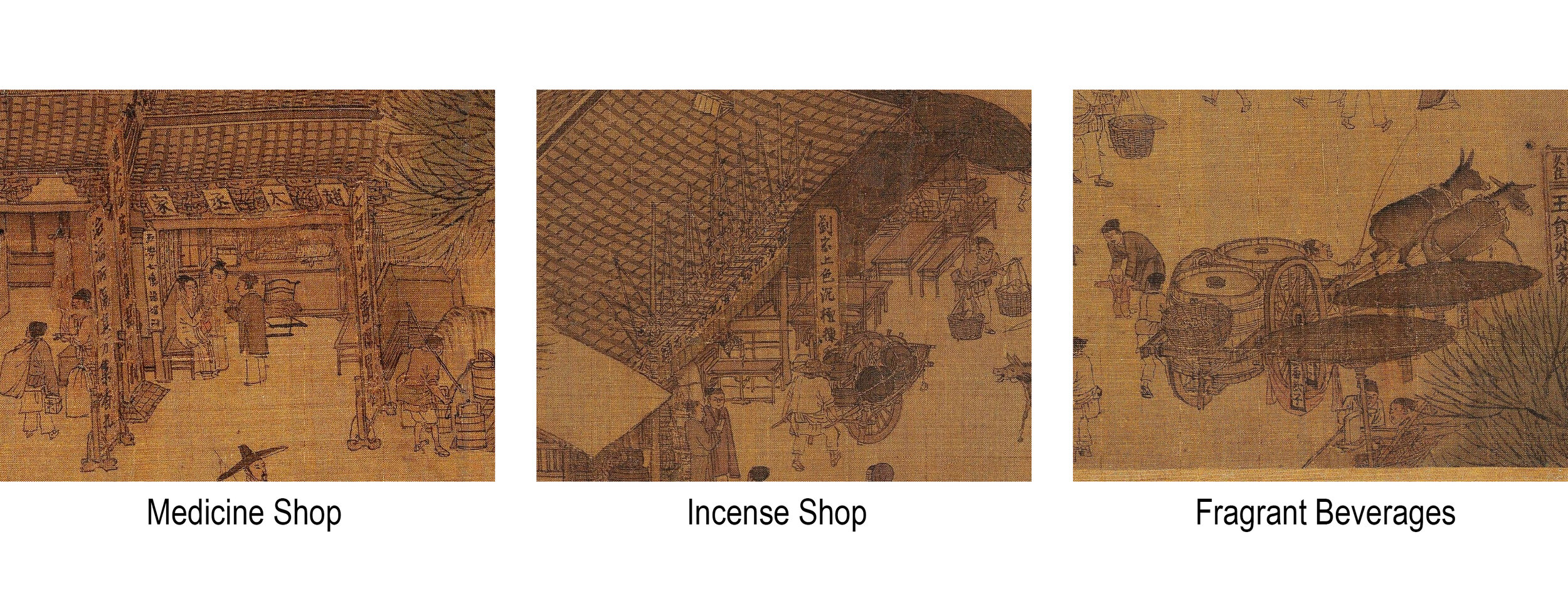

References to aromatics can be found in multiple locations of the Qingming Shanghe Tu. The use of aromatics, or fragrant materials, were so woven into the culture and economy during the Song dynasty that it follows that they would make their way into the depiction of a busy marketplace and dynamic urban scene. Inside the gates of the city there is a small shop marked by the sign “劉家上色沉檀楝香鋪” or “Liu’s house of high quality, agarwood, sandalwood, and frankincense,” with another sign that indicates the shop also sells blended incense fragrance. Incense culture at the time was becoming more widespread, and amongst the Song literati it was considered as one of the four sensory practices to be mastered, including flower arrangement (touch), tea (taste), and painting appreciation (sight).

Whether used spiritually, socially, or for cosmetics, experimenting with incense fragrance was a means of refining one’s sense of self. The public availability of these aromatics as commodities—while still luxuries aimed at the elite—mirrors the fact that they were no longer permitted for use only by the noble class but were available for anyone to purchase if they had the means to do so. The imagination and influence of aromatics was so great that it spread throughout the social classes, even inspiring beverages and snacks infused with scent as more modest means to try a taste of the exotic. Small, informal street stalls selling these “fragrant beverages” are seen in the painting. Perched under an umbrella on a roadside stool one could find refreshment with an aromatic elixir, possibly made of rose water or white plum, sandalwood or shiso leaf, and watch the small dramas in the street unfold.

Whether used in incense or as a beverage, one important dimension of aromatics was their benefit as medicine. In something simple like an elixir the aim could be to cure a hangover or to give a quick boost to one’s vitality and mood, but when combined as incense and burned the medicines had powerful effects—such as influencing qi and the body’s internal elements, evoking certain states of mind, or as we more fully understand today, purifying the air with the antibacterial properties of the natural material.

The last place we clearly see the presence of fragrant materials is in one of the painting’s pharmacies. The signs advertise blended incense tablets for common ailments. An aromatic like Frankincense, brought into the city from the far off reaches of the Arabian Peninsula or North Africa, could be not only burned but could also be dissolved in water and administered as a medicine. The presence of aromatics in the painting tell a story of not only of the aesthetics of Song life but of the desire people had for connection with distant places. The array of aromatics available at the time reveals the reaches of empire, both to the remote and little known borderlands within its realm as well as to geographies that stretched around the globe. An urge to experience something different with one’s senses was a way to push the known limits of both the mind and body.

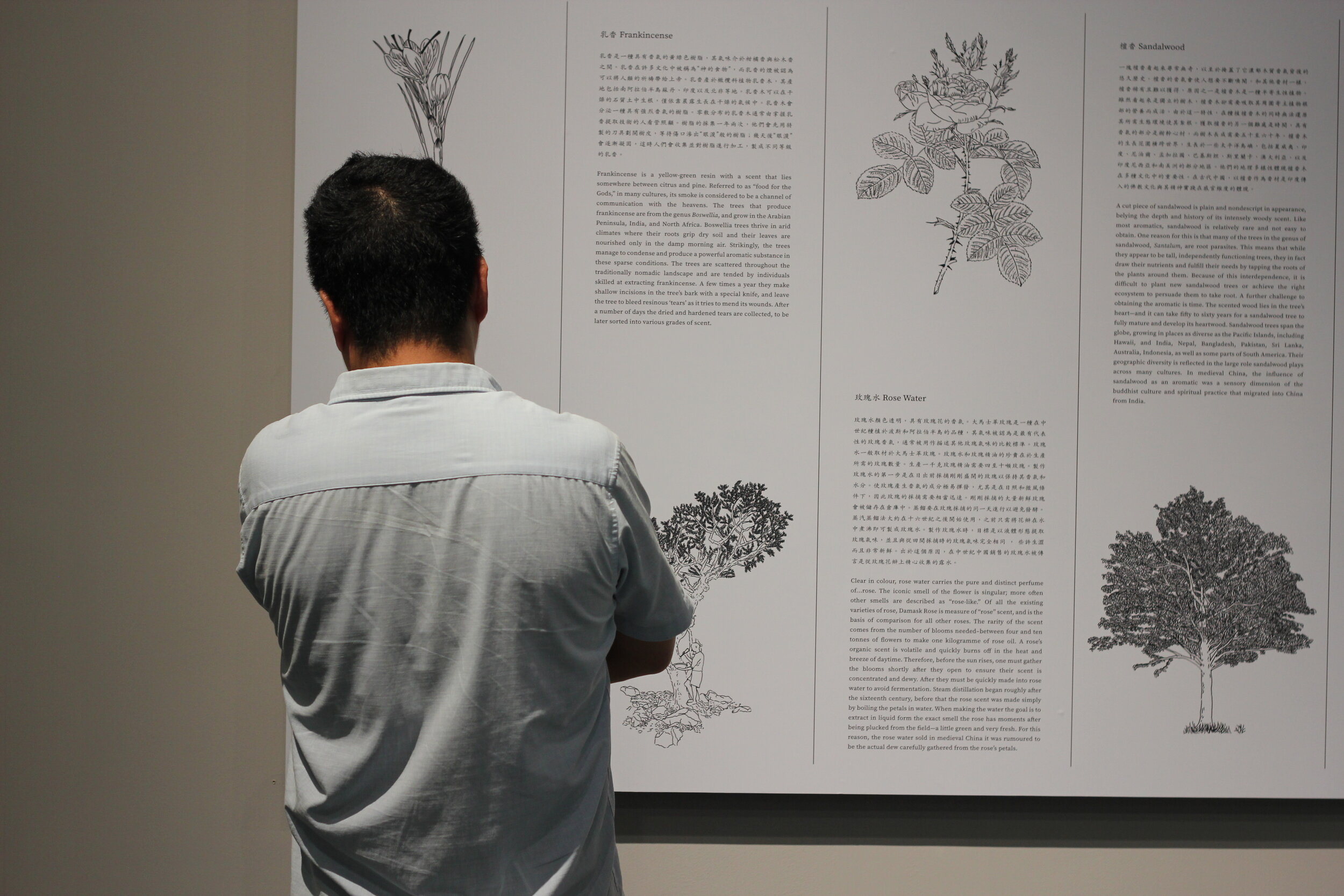

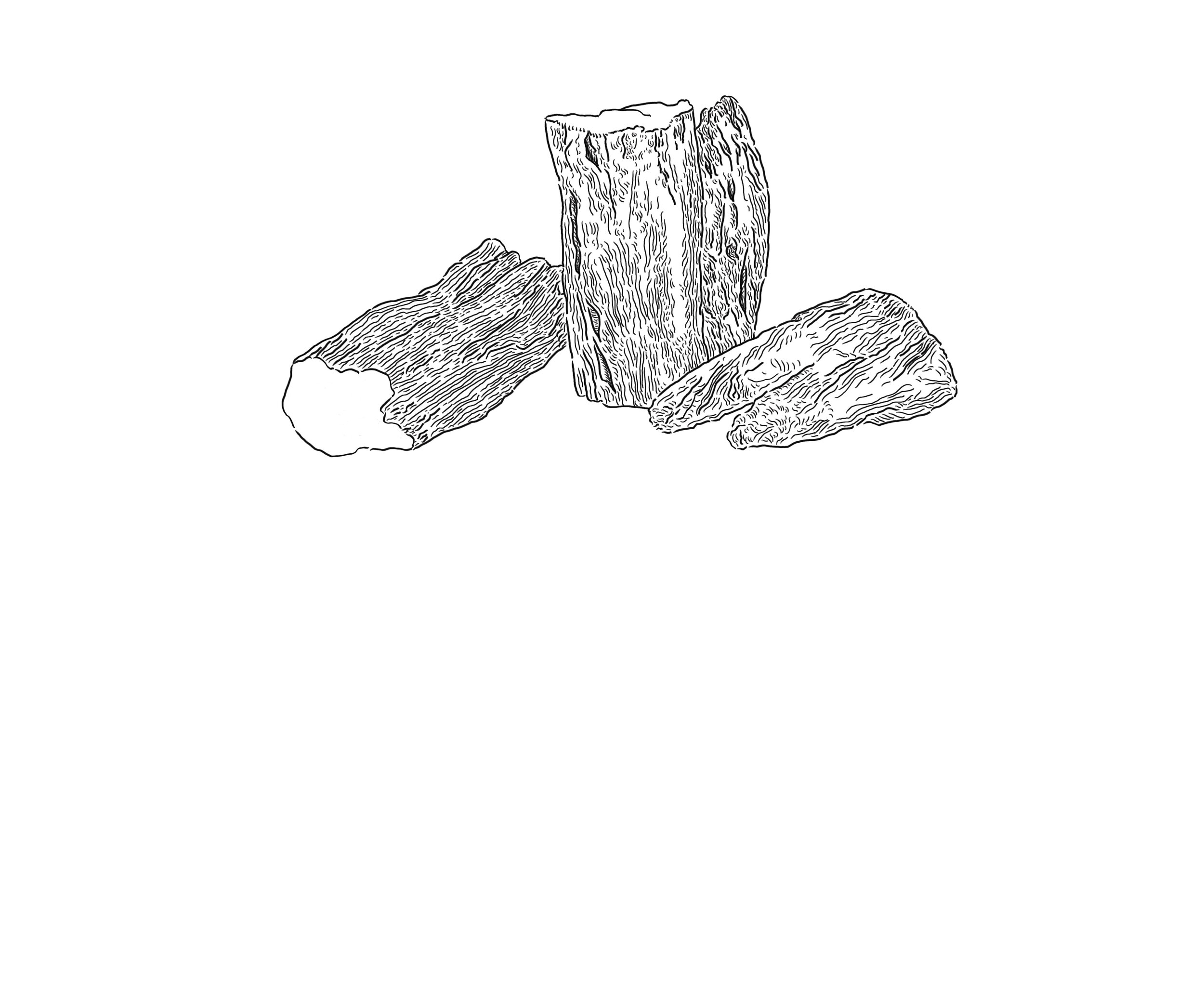

Aromatics

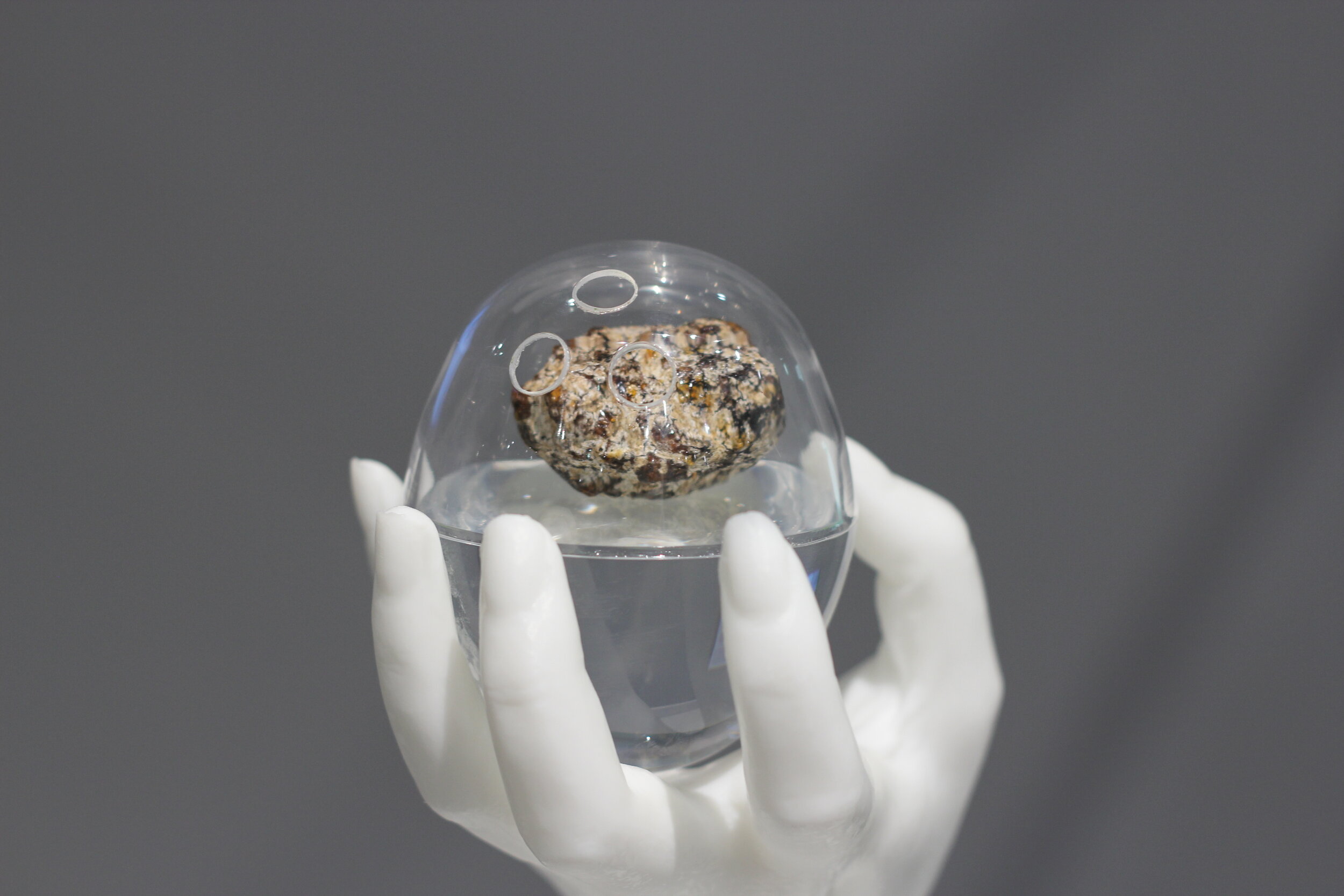

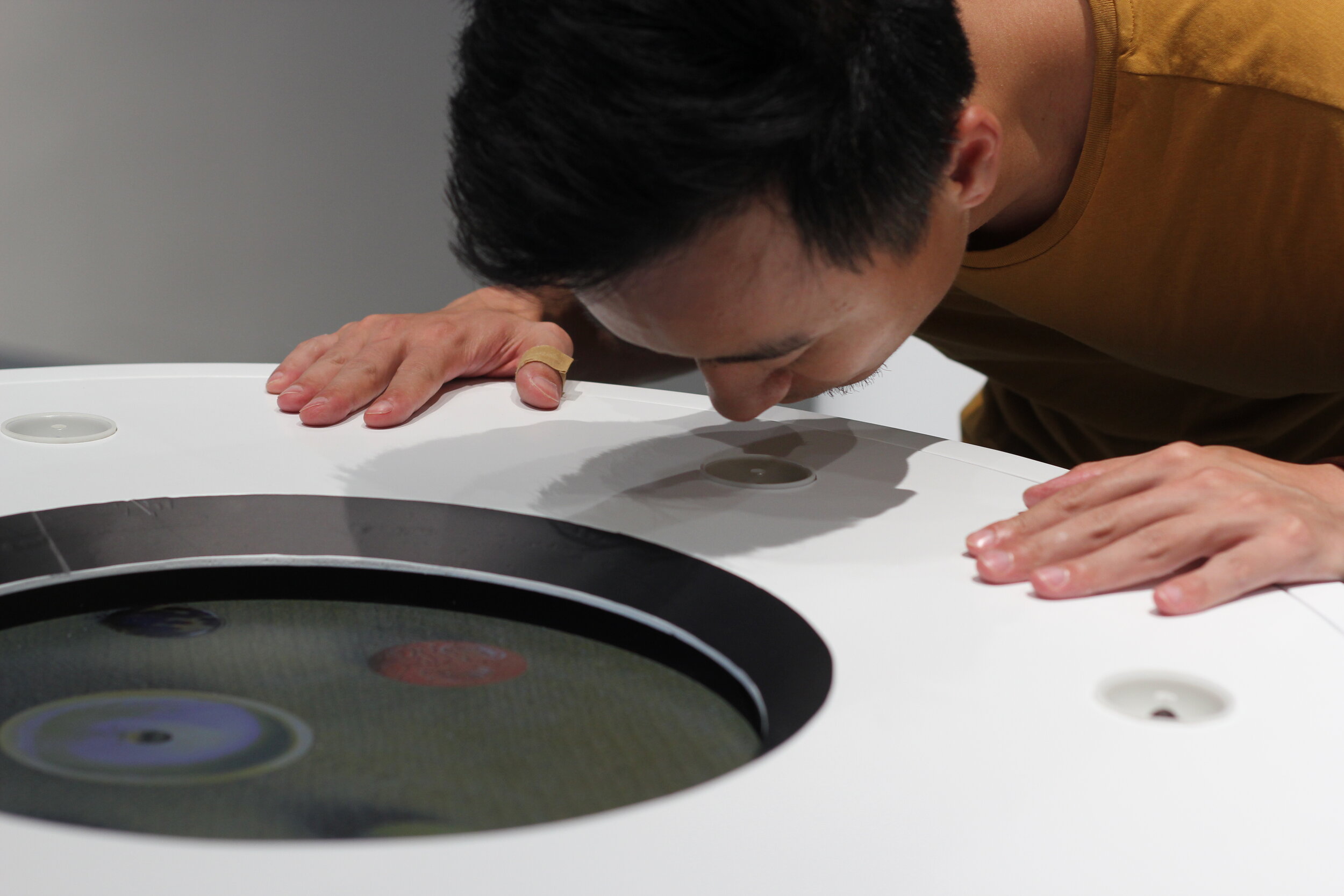

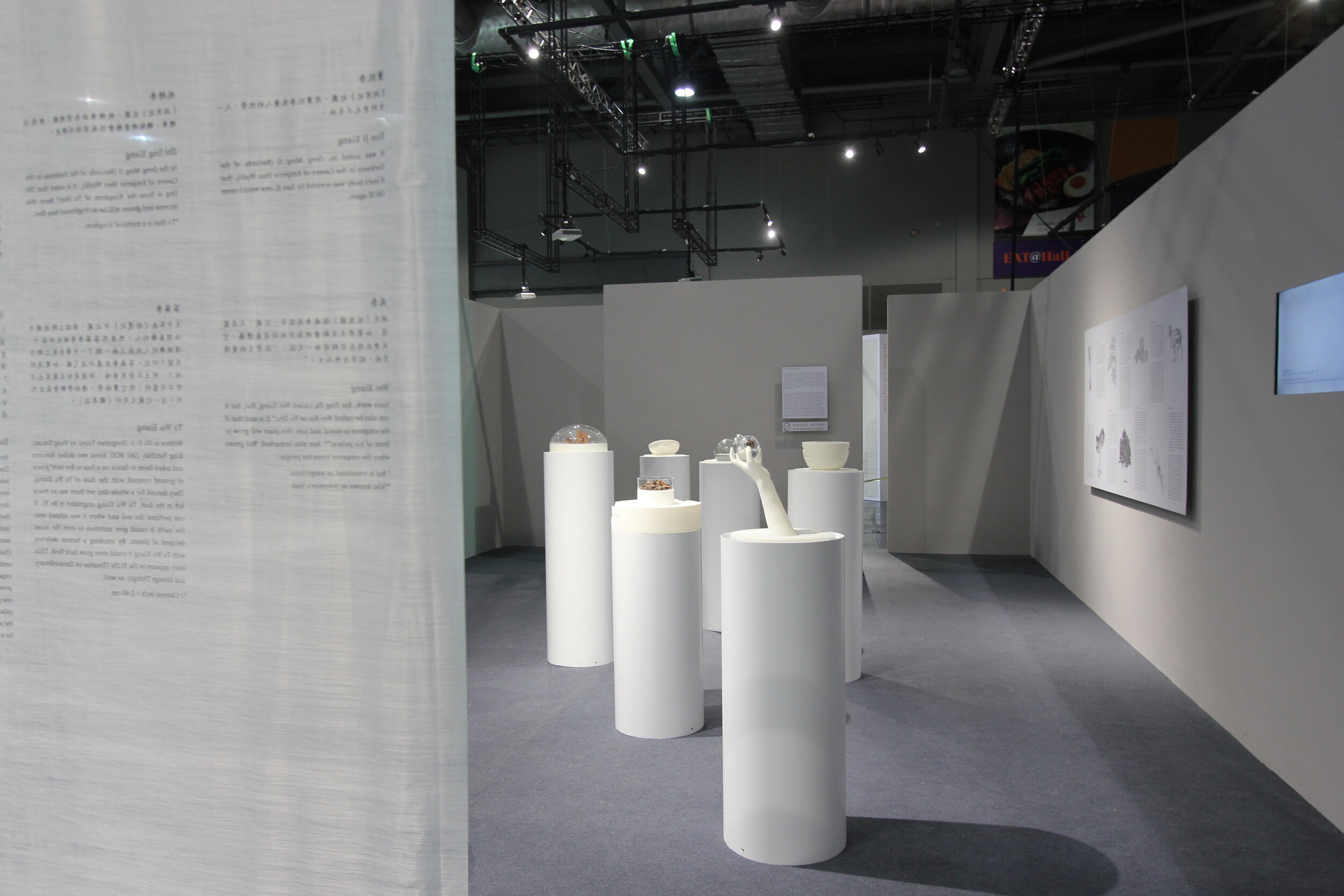

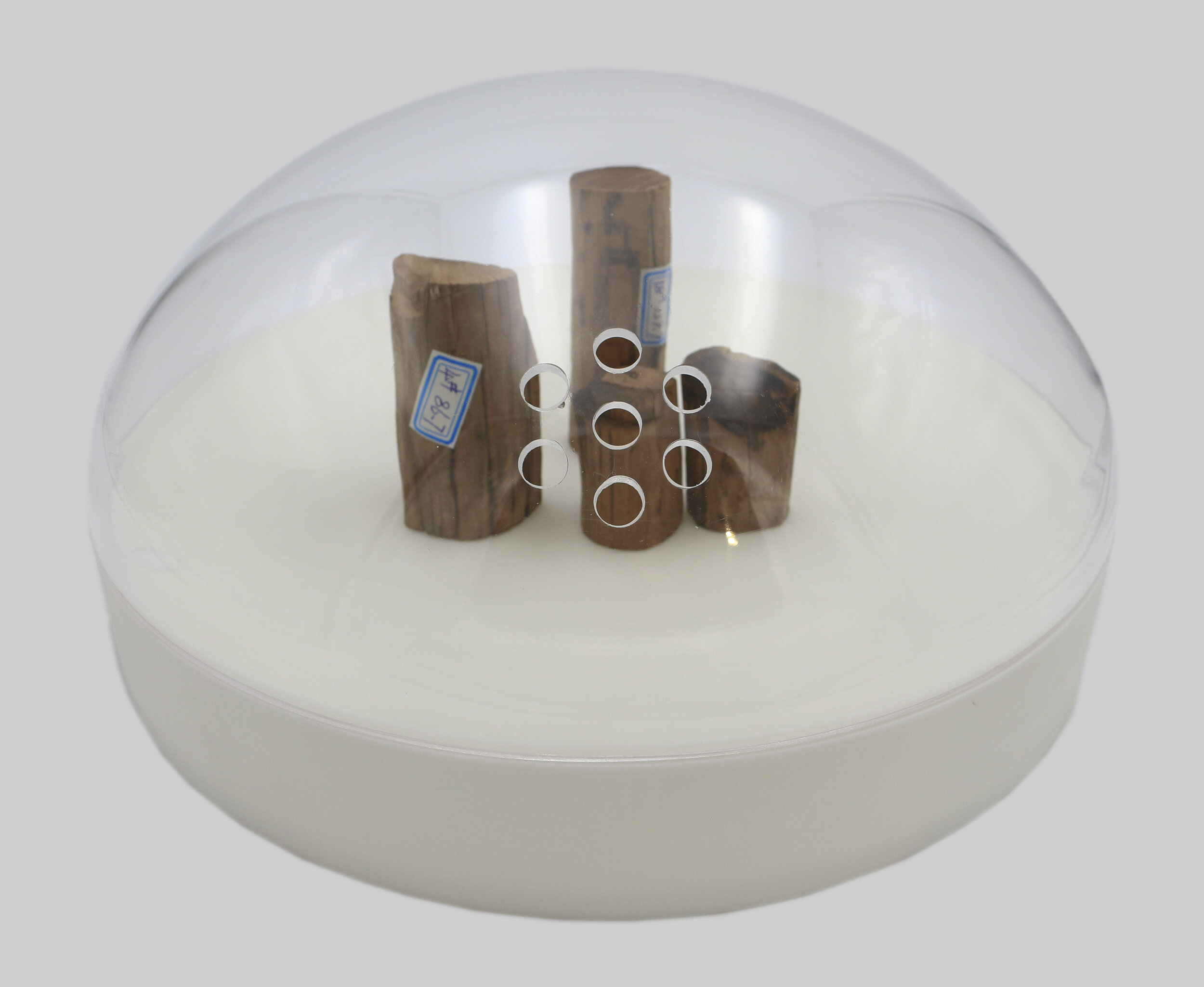

Investigations into the physical phenomenology of smell — led to the design of a series of vessels, each conceptualized to fully maximize the sensory experience and help make something as elusive as scent, somatic and embodied, tactile and tangible. Observations about the body’s response to each aromatic’s individual smell informed the shape of each vessel, in order to help the body further lean in, draw back, take a quick whiff, or nose around for different notes. Additionally a sonic layer accompanied each pedestal helping to slow down perception and help the individual tease out different layers of the aroma presented through a hypnotic repetition of various scent descriptors. The installation offered an effective means of translating the olfactory realm into an architecture for aesthetic, creative, interactive space. The the seven raw aromatics presented, and two blended incenses, were of particular relevance to the scroll and the Song Dynasty.

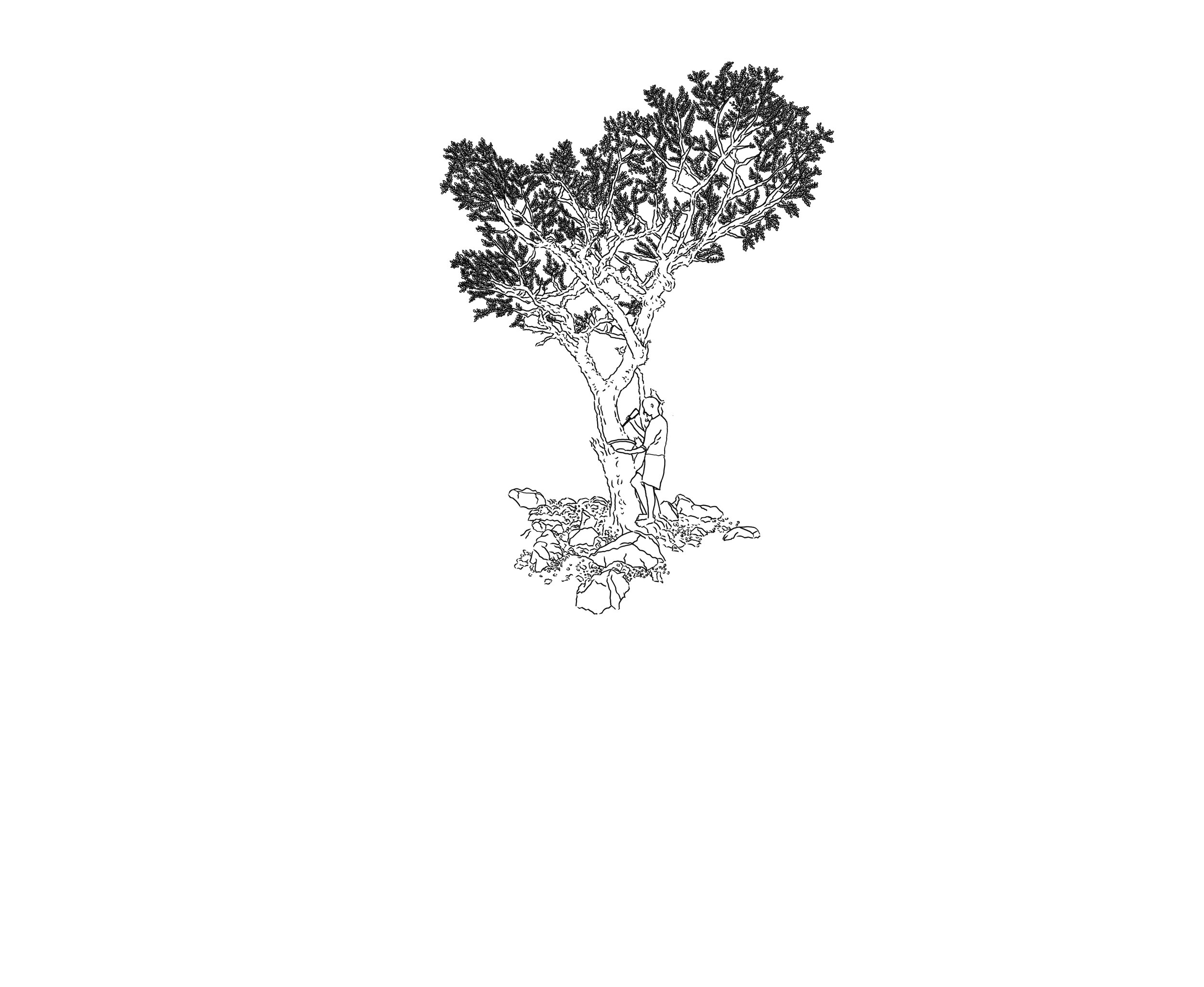

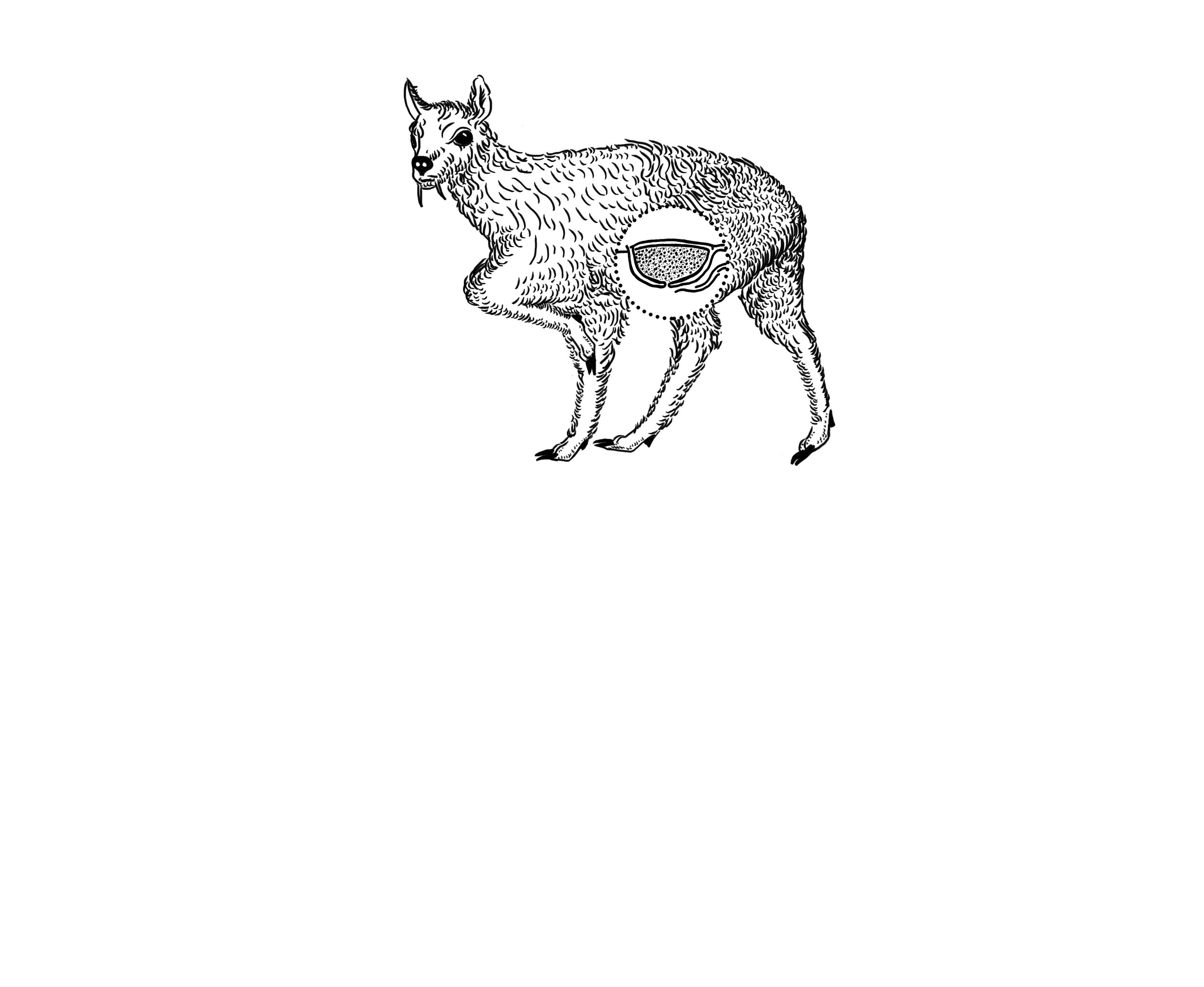

Plant & Animal

The aromatics shown here were amongst the most important in the Song Dynasty in terms of use, trade, and profit. Their scent is a living archive of the history captured in the Qingming Shenghe Tu. These materials draw from the botanical, mineral, and animal realms. In nature, the intense concentration of a scent typically indicates something not only rare, but potent in its sensory and medicinal effect. These scents arise either in extreme conditions or are the result of the painstaking efforts of humans to cultivate and collect them. Because of this, many of these materials are comparable to the price of gold. Valuable not only in Chinese culture, each aromatic—bearing a multitude of names—has its own place in the larger global narrative and long history of the human obsession with scent.

Investigations into the physical phenomenology of smell led to the design of a series of vessels, each conceptualized to fully maximize the sensory experience and help make something as elusive as scent, embodied, both tactile and tangible. Observations about the body’s response to each aromatic’s individual smell informed the shape of each vessel, in order to help the body further lean in, draw back, take a quick whiff, or nose around for different notes. Additionally a sonic layer accompanied each pedestal helping to slow down perception and help the individual tease out different layers of the aroma presented. The installation offered an effective means of translating the olfactory realm into an architecture for aesthetic, creative space. The aromatics presented each have a complex global history of their own, for incense, medicine, food, and perfume — but these seven were of particular relevance to the scroll and the Song Dynasty.

Trade in Aromatics

Aromatics were an ideal material for trade because they were relatively lightweight, stable as commodities, and extremely valuable. Because they were so profitable, the Song government strictly regulated and taxed their trade. The diversity of materials available also increased as the growth of maritime trade opened new territories for exchange and brought in products not available from overland routes. Expansion of imports in foreign and rare aromatics into the empire aided the development of incense culture within its society. Scent was also a basis of cultural exchange as the influence of seemingly exotic aesthetics and philosophy was carried by these material goods. Furthermore, aromatics, both foreign and Chinese in origin, were commodified for export with places outside Song borders, which not only created profits for the empire, but also helped spread the influence of Chinese incense culture to many other realms. From a medicinal and spiritual standpoint, aromatics brought from afar promised miracle cures not accessible in local territories.

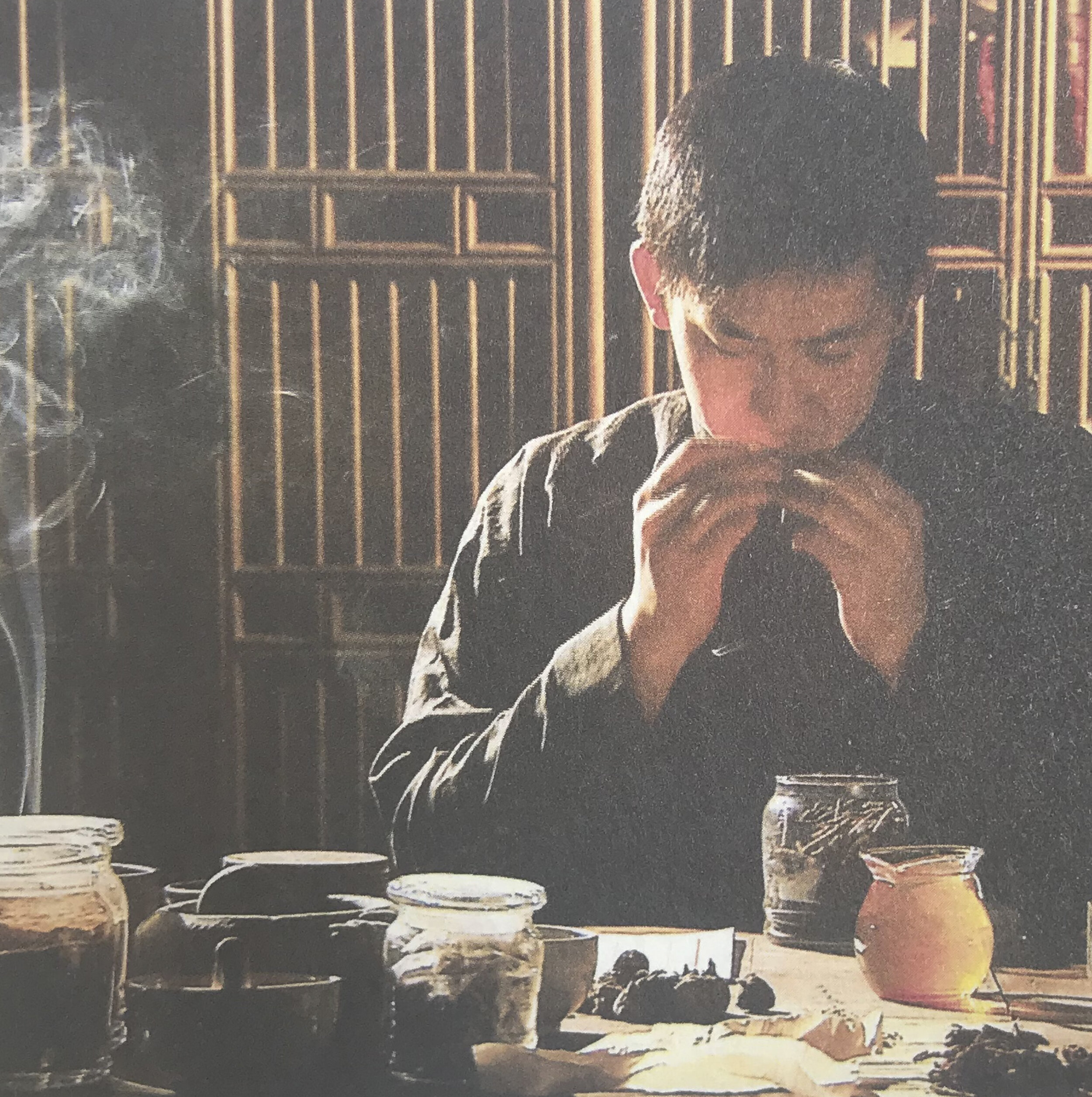

Song dynasty incense making.

Song dynasty incense ritual.

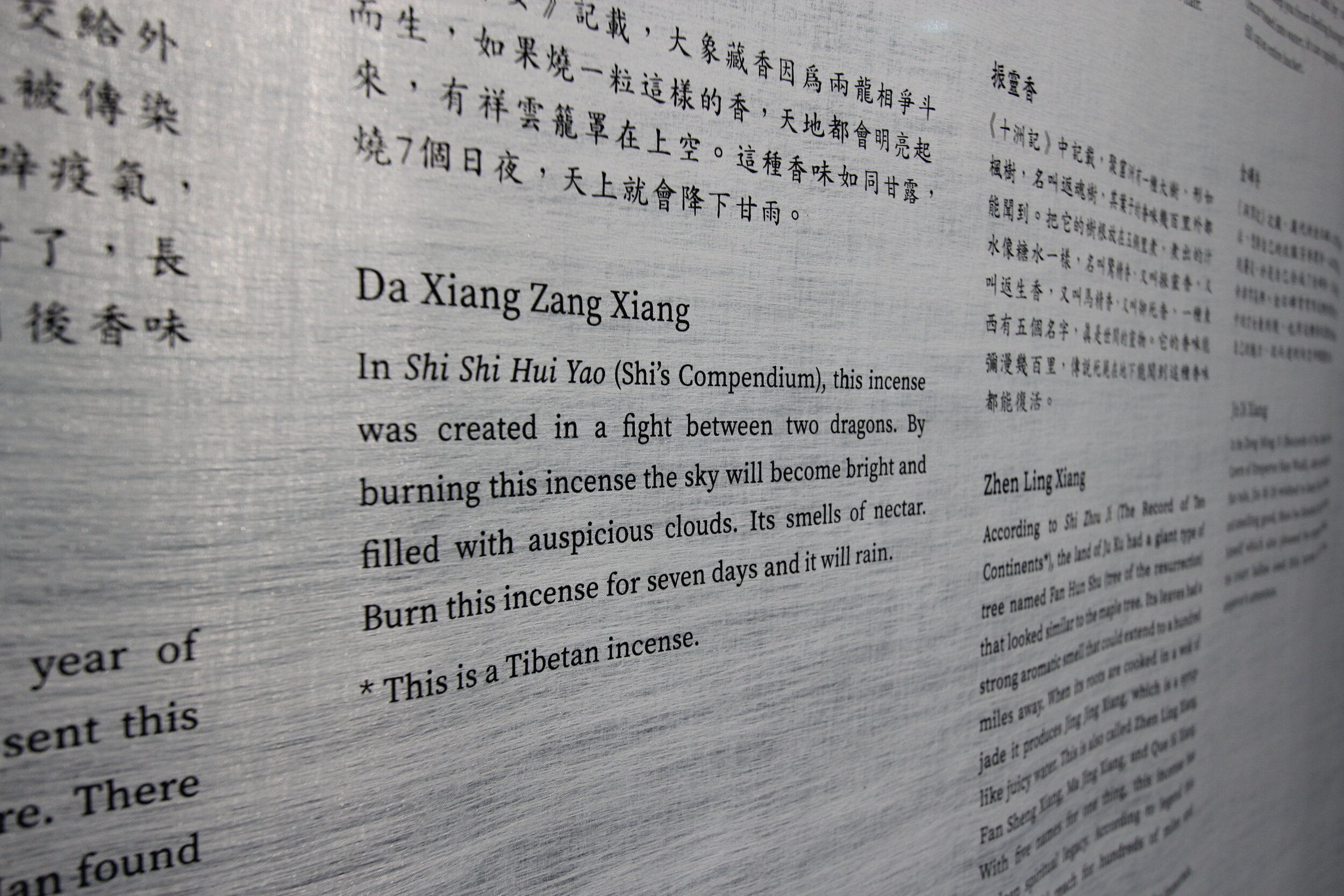

Strange Fragrances

洪芻 香譜 is known as Hong Chu’s Xiang Pu (The Fragrant Spectrum) and was believed to have entered wide circulation sometime between 1082-1155 CE. Xiang Pu is a genre of reference texts documenting incense culture that was first developed in the Song Dynasty. These texts helped both to classify and identify the plants and animals involved in aromatic trade, gave information about how to appraise their quality or identify fake goods, offered recipes for blending incense, and in the case of the Hong Chu Xiang Pu, documented some of the strange tales associated with incense use. The stories are short anecdotes the author complied from various historical texts and offer a glimpse of the beliefs that were attached to powerful aromatics. The anecdotes range from the supernatural, with claims of certain scents being able to raise the dead, to the mundane, with recommendations of which fragrances might be used as shampoo.

Process

In order to situate the project, extensive research was done not only into the history of the Qingming Shanghe Tu and the historiography of its scholarship, but into various aspects of the Song Dynasty, including the history of Chinese medicine at the time, and into various aspects of incense — such as the artistic, cultural, and medicinal uses of incense by Song literati and the Song court, incense use in the preceding Tang dynasty, the Song dynasty’s civil regulation, commodification, and global trade of aromatics, and the spread of incense culture— first into China via India and the Middle East, and then on to Japan, Korea, and other parts of South East Asia.

Each aromatic researched came with its own long and complex global history from the Middle East, India, Africa, South East Asia, China, or other locale.

The majority of this research was based on secondary sources and histories, with consideration of a few key primary sources. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of the research into this traditional material culture came from people working today to keep this heritage alive and thriving. Song incense practice and scent formulations are not something relegated to the pages of a book — but are very much a continuing part of incense culture and are accessible today.

Li Shiliang 李時亮 inherited his knowledge of medicinal incense practice from a family lineage of practitioners five generations long. Several visits to his studio in Beijing and interviews with him gave insight into the intersection between traditional medicinal theory and incense making and use—including challenging our understanding of incense in what we more commonly think of as its aesthetic dimensions. His company’s global trade in large quantities of aromatics for incense making and his own personal history of aiding China through the donation of medicinal incense during outbreaks such as SARS (and now COVID) gave a striking new perspective into the extent and impact of incense culture more generally. He generously loaned precious incense materials for the exhibit in Hong Kong.

Professor Liu Jing Min 劉靜敏 teaches at the National Taiwan University of the Arts and is an expert in Incense history and culture. She wrote the book, a Study of the "Xiang Pu"(Book of Incense) of the Song Dynasty (宋代《香谱》之研究). We were able to interview her by telephone and get a very specific overview of her scholarship into incense culture and trade at the time of Song. Her teacher, Liu Liang-yu 劉良佑 is generally considered to have founded the field of incense scholarship and wrote the book, Chinese Incense Culture (香學會典).

Xiao Mu 肖沐 is an incense expert with a studio also based in Beijing. In a series of visits with her she gave us a detailed understanding of both the interactive qualities of various aromatics, but also and understanding of the process of making the types of incense “tablets” used in Song times. Her generous demonstrations of making blended scent, as well some details of Song-style incense ritual practice were featured as videos in the installation.

Credits:

Exhibition Curator: Beatrice Leanza

Overall Exhibition Designer: Nicola Saladino & reMIX Studio

Overall Visual Identity: Studio NA.EO

The Incense Room multimedia installation: ATLAS Studio