Chinese National Museum of Ethnology

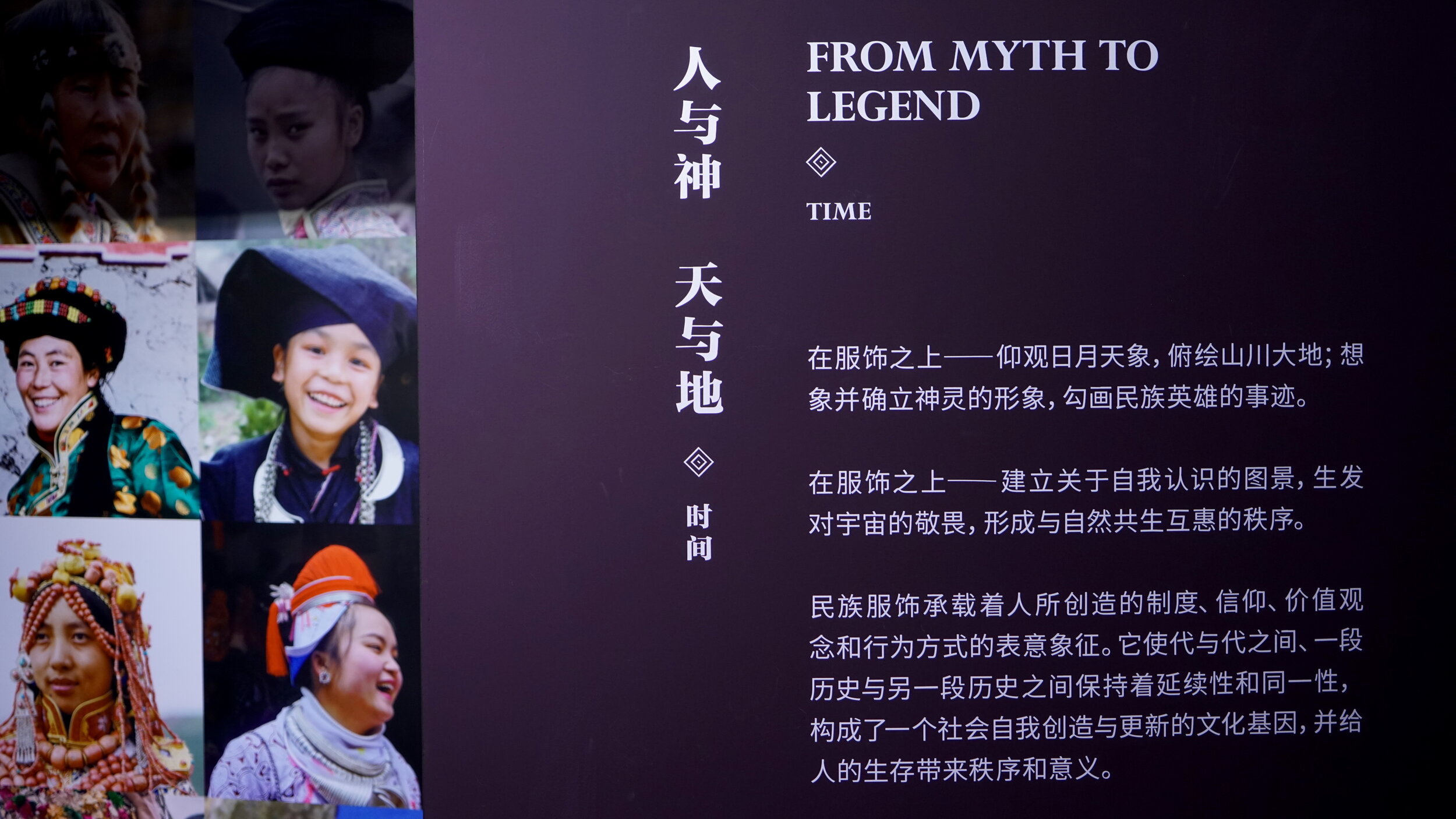

Tradition @ Present opened at the Ningxia University Museum in 2016. The Chinese National Museum of Ethnology, located in Beijing, houses incredible collections and produces original scholarship — but they have no permanent museum space of their own. This show was conceived of as a traveling exhibit designed to showcase a portion of the incredible collection of ethnic textiles belonging to the National Museum of Ethnology. The textiles in the collection come from dozens of distinct ethnic minority groups, every imaginable geographic terrain in China, and date roughly from between one hundred years-old to the present. In other words, these artifacts reveal a somewhat contemporary glimpse of the incredible diversity, people, and cultures that exist across China’s varying landscapes. Unlike with industrial processes, these textiles and clothing can not be understood as circulated commodities — carrying semiotic meaning split and floating free from the making — they are instead artistic processes that manifest as a material objects in complex social and ritual systems. In many ways these artifacts can be understood as non-linguistic texts, carrying meaning and narrative from person to person and from generation to generation, creating social bonds that extend far beyond the textile itself.

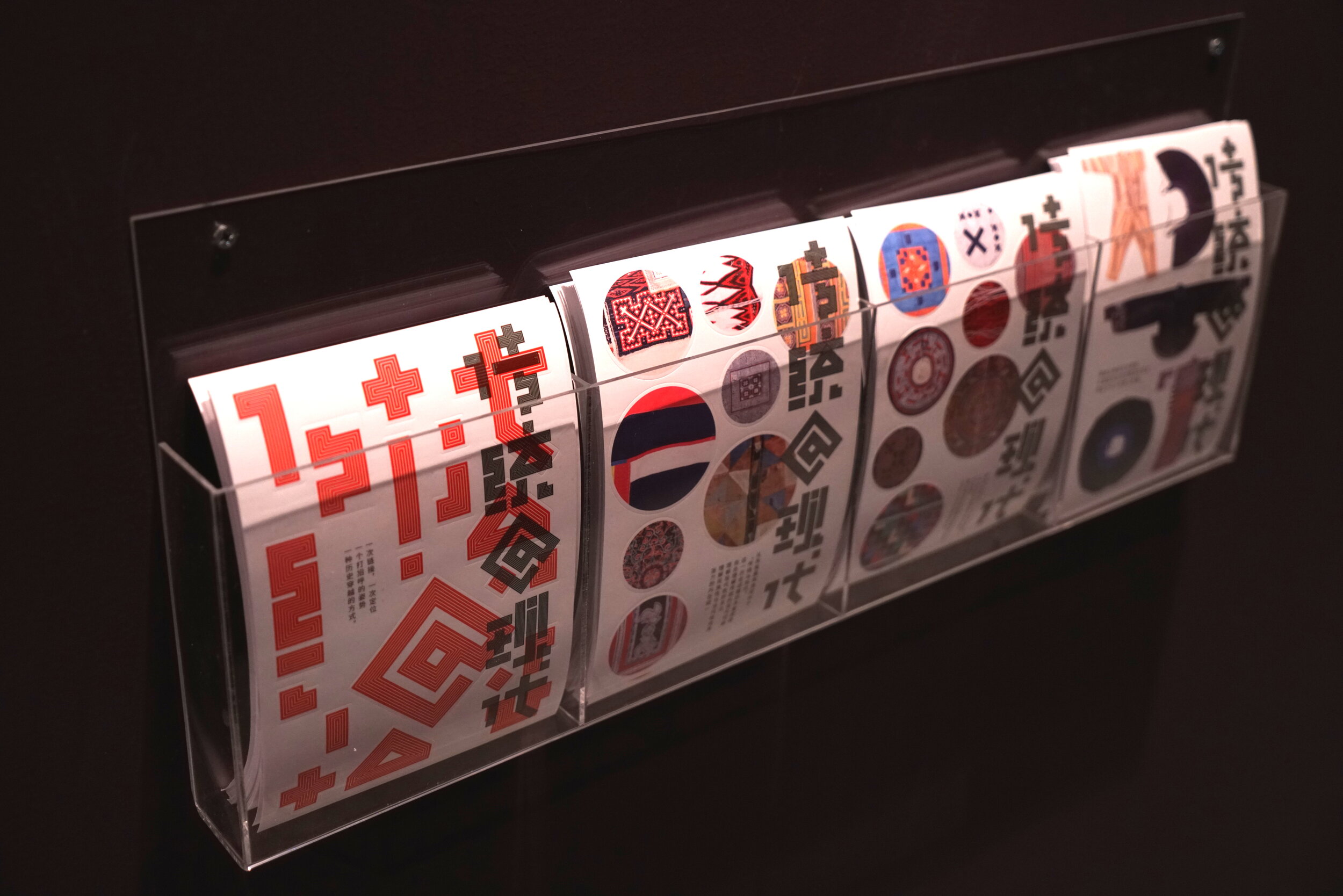

The curatorial team divided the exhibition of over 200+ artifacts into four distinctive parts, Time, Space, Craft, and Continuum.

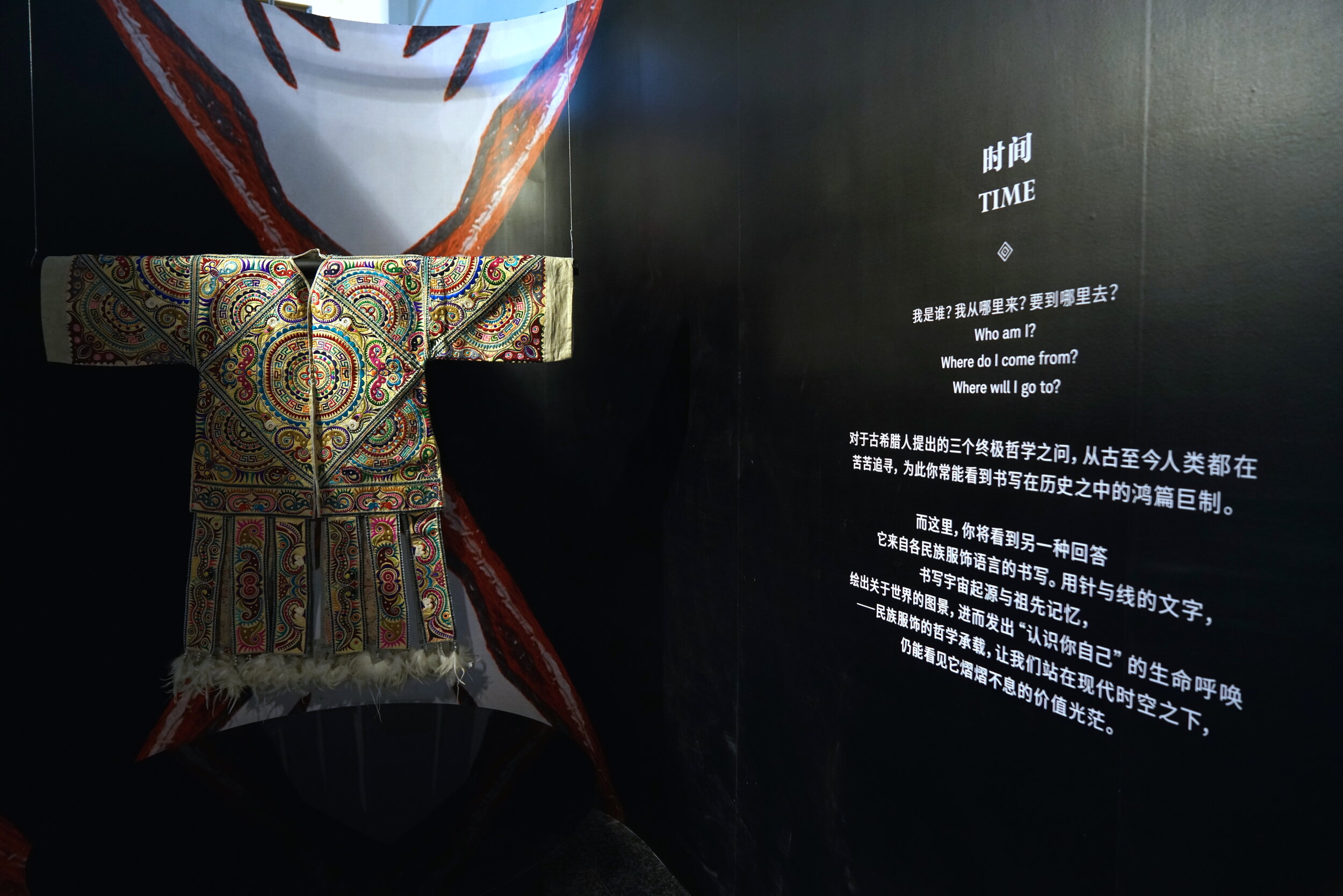

The introduction, and arguably most foundational part, of the exhibition centers on the perceptions, use, and measurement of time in the realization of individual identity and in the understanding of one’s relationship to the universe and the social whole.

Who am I? Where do I come from? Where will I go?

The exhibition opens looking at various creation myths through geometry, symbol, and form. It asks us to consider, How did the universe get its shape? What is the origin of life? and What is the way back home? These ritualistically important pieces of clothing carry the story of the creation of the world and serve as a direct link to one’s ancestors.

This is followed by a consideration of how making textiles and cycles of time intersect throughout the day, the year, or one’s lifetime. The four seasons guide the different stages of textile craft, especially as one’s own time must be balanced against the cyclical demands of farming. One piece that embodies this concept is the 365 fringe skirt of the Yi minority — the skirt takes a year to make as it is done slowly, made one fringe a day, for an entire year — before being completed.

Key milestones of time are birth, marriage, and death. Baby carriers and children’s hats are often the most elaborate pieces crafted, holding extraordinary levels of detail and meaning. The hats often represent animals are made to be protective — using the animal spirit to ward of evil or illness from the child. A connection to the divine world, in ritual and in death is embodied in the making of very special pieces both for the deceased or for those who are entrusted to execute key rituals. Lastly, wedding clothes showcase an incredible diversity of costuming and are often the most exaggerated in terms of boldness of color, transformation of the body and form, and layering.

The exhibition design was a collaboration between ATLAS Studio, 2X4 Beijing, and the National Ethnographic Museum.

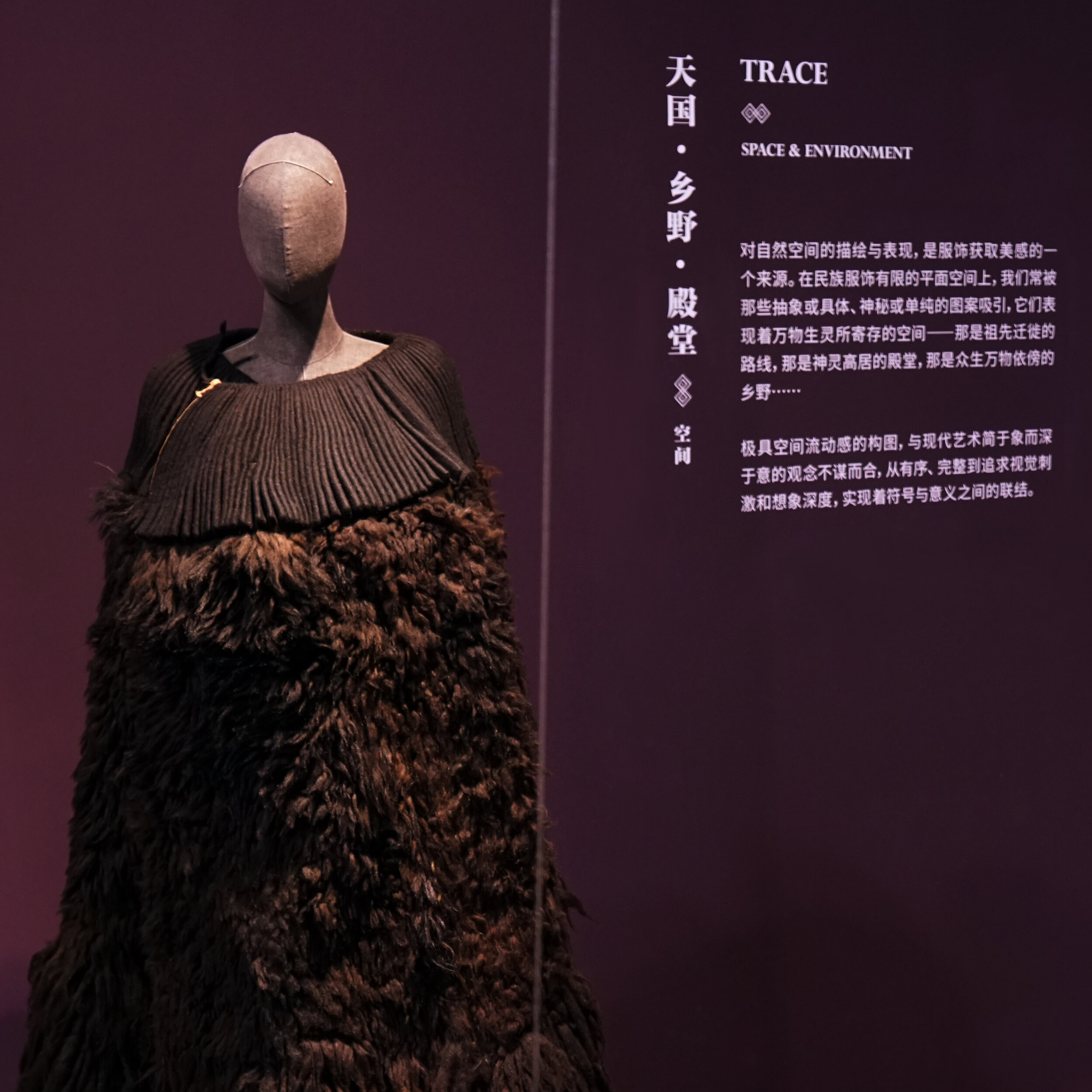

The second section on ‘Space’ took into consideration the connection the clothes have with the larger environmental context. The first consideration of space is concerned with the formal, clothing, developed from hand-woven cloth is flat and planar in its design — so as not to waste material with cutting. The way the clothes hang around the body — and then the way the body thus costumed, adapts to the physical space around it — were explored. Pleated skirts — that lie flat in giant circles — are widely made amongst many groups. The other dimension of space relates to geographic terrain, landscape. Many of the clothes reflect the diversity not only of climate from which they come, but also the natural materials available in any one environment. Take for example, the entire suit of fish-skin clothing displayed that was made by the Hezhe people who live along the Heilongjiang River.

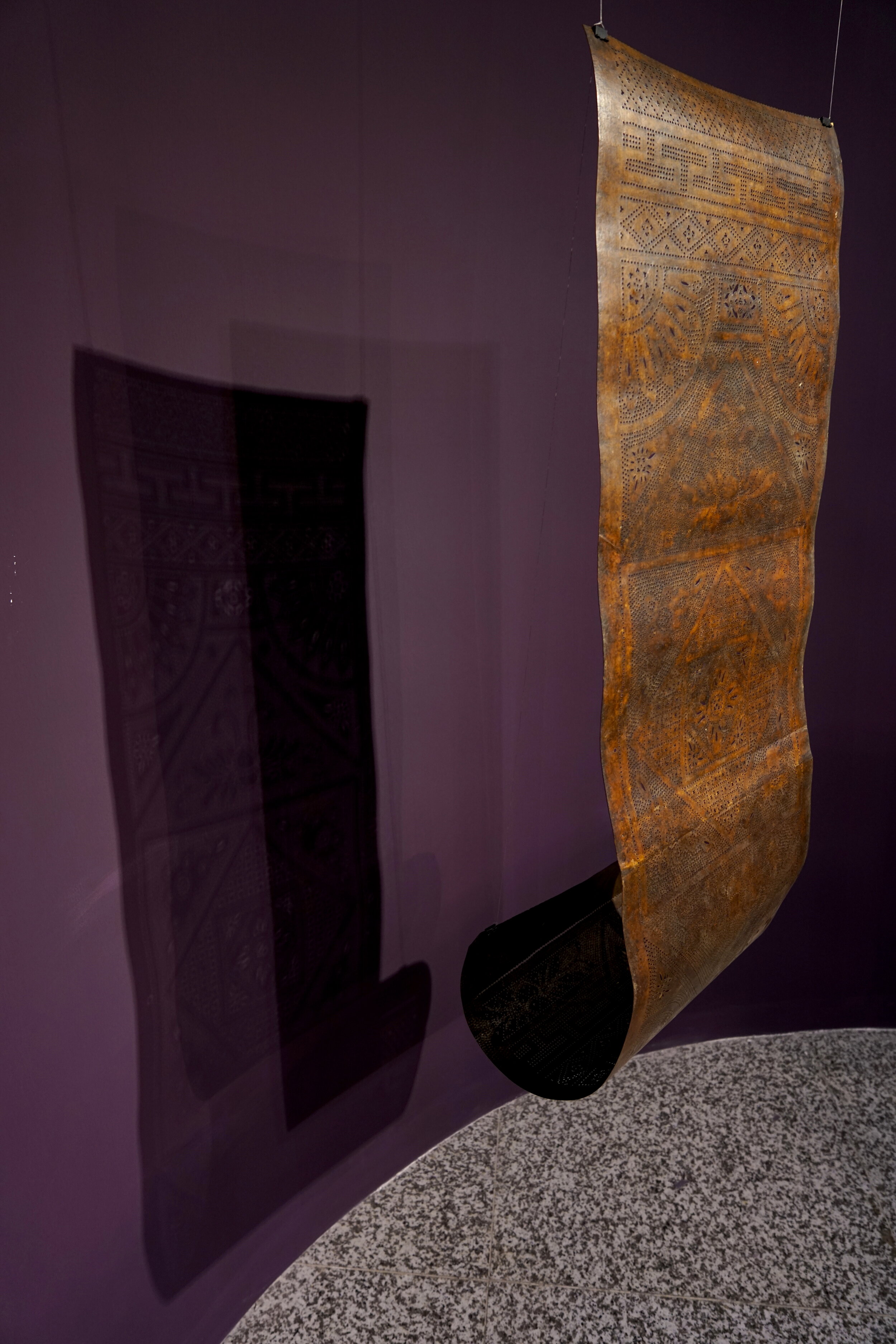

The third section on ‘Craft’ looks in detail at the myriad of ways these textiles are made. Oftentimes the design of the tools is just as elaborate and ornamented as the textiles— they are small works of art unto themselves. A contrast is drawn between our conception of the ‘machine’ in the modern-era and these traditional tools for transforming natural materials into cloth —such as complex spinning wheels and various kinds of hand-looms, from back-strap to free standing. Extending from this — many samples of various weaving styles are presented, revealing the incredible complexity and expression of imagery that is made possible with these relatively simple looking tools. The geometric patterns create a kind of language that can be read, encoding information about the landscape, local plants, animals, people, narrative events, and cosmologies each community is immersed in. Embroidery carries this theme even further — allowing for individualistic artistic expression to exist alongside more traditional patterns and forms. In this section the connection can be directly made between the natural materials that are painstakingly transformed into pieces of functional art, and the fibers, plants, minerals, and dye materials are laid out to explain in detail their ethnobotanical importance and interrelationships.

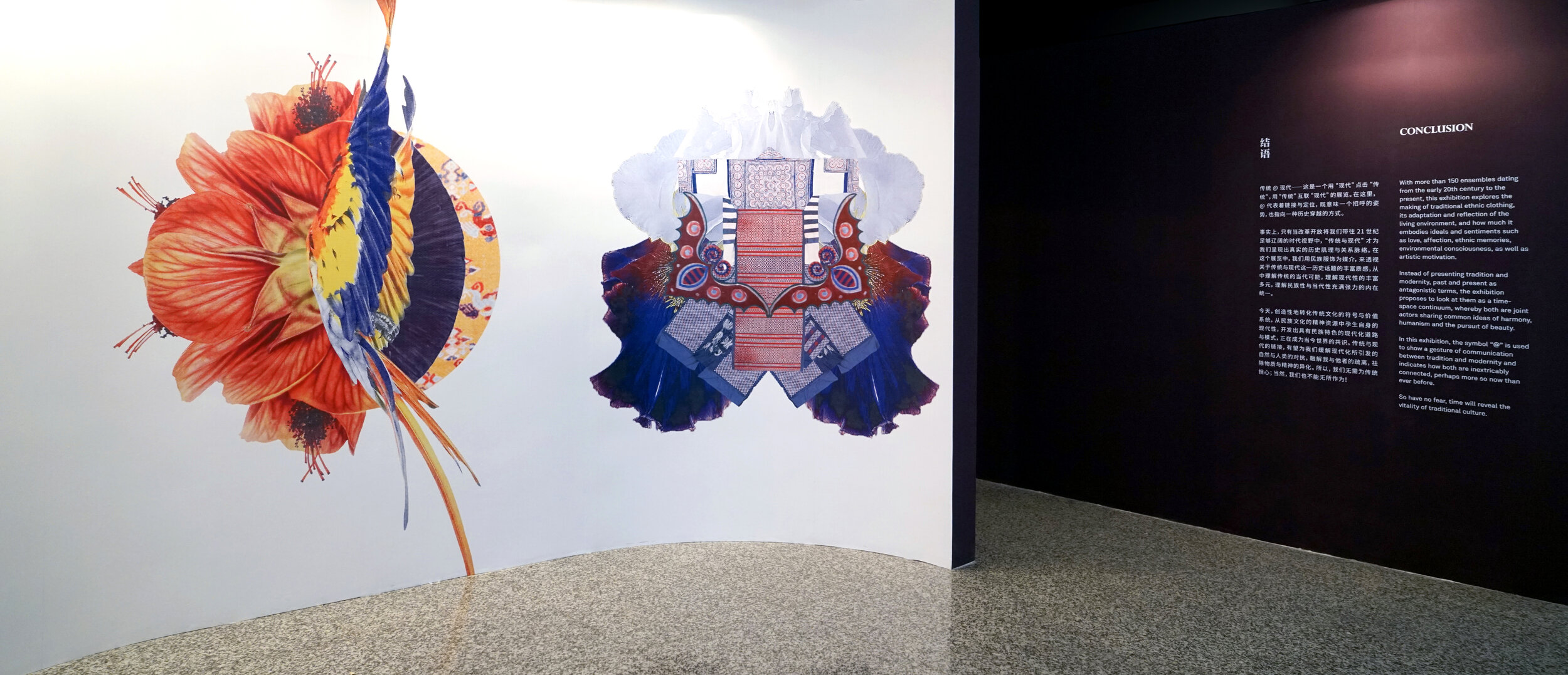

The last section of the exhibit ‘Continuum’ asks us to reconsider our fixed and limited notions of ‘luxury’ in what we buy and use in our lives. So much of our perception is shaped by the ecology of branding and marketing — this section asks us to take a second look. Seeing these textiles, many of which take years to make and hundreds of hours of labor, we can understand the meaning of a more lasting luxury, not only that of time spent, but of a deeply rooted and direct connection to one’s heritage, family, community, and ancestors. This section paired textiles with contemporary fashion items to suggest a transformation of perception. Beyond this a graphic landscape was presented that played with motifs and themes in the clothes, stickers with more patterns and details were created and the audience was invited to begin to transform these traditions for themselves through a direct interaction with the space — giving them the opportunity to be both in the continuum of tradition and to make their own mark.

The process…

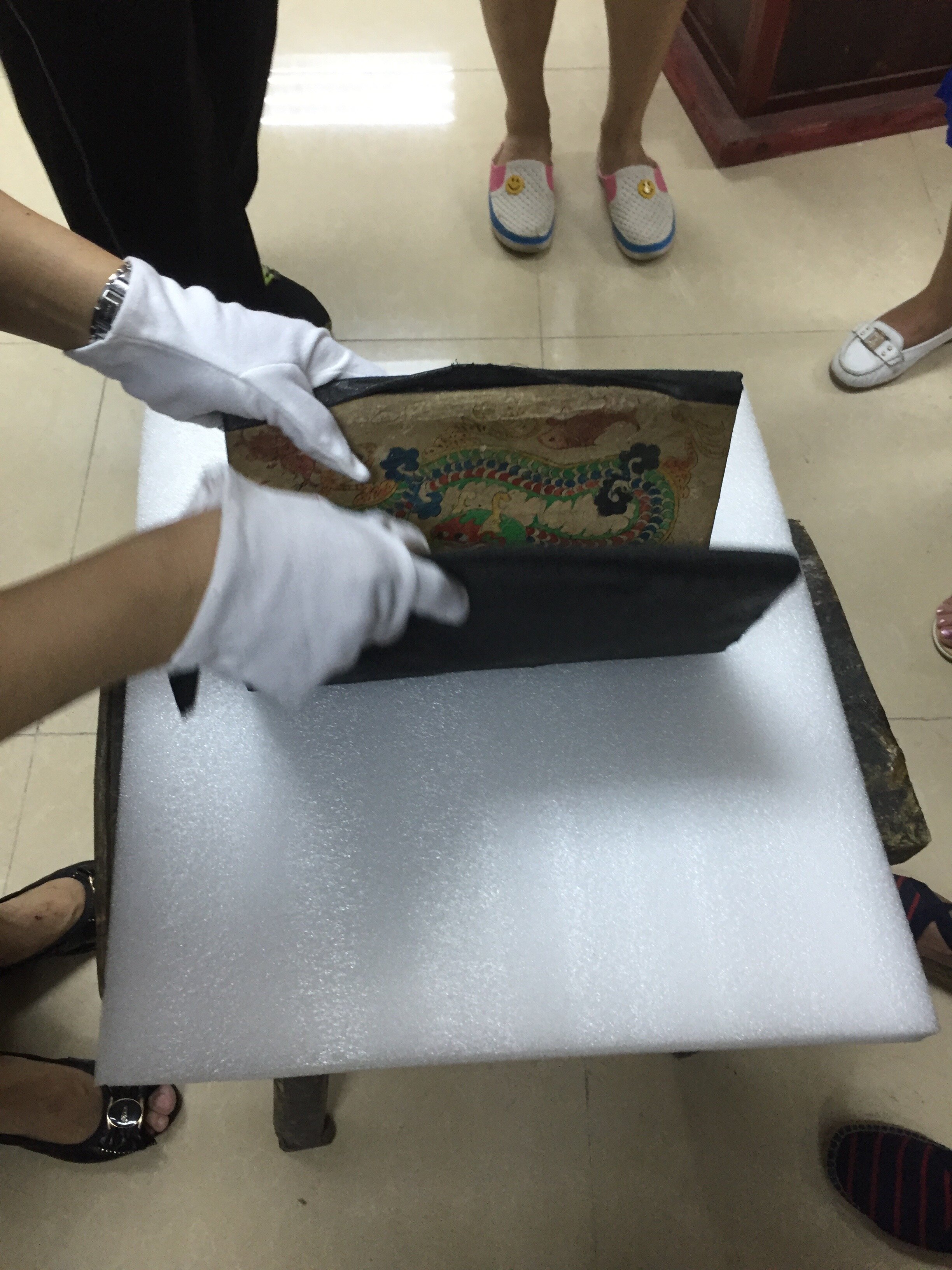

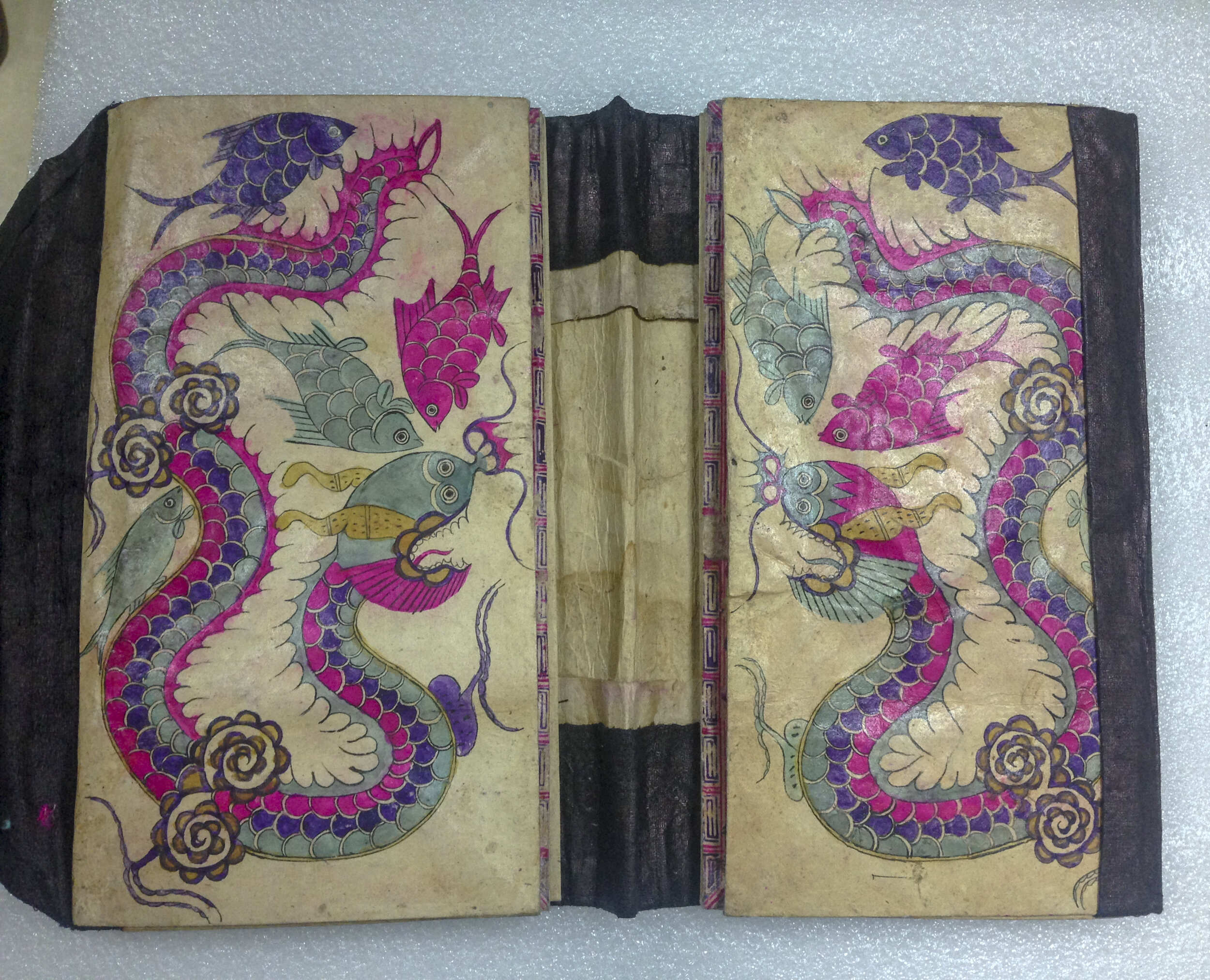

The process of making the exhibition led to an incredible exploration of cultural heritage and access to a remarkable collection of artifacts. The National Museum of Etnology is home to a vast collection, but as of yet has no museum space. Understanding the content for the exhibition meant entering the archives and opening drawer after drawer of perfectly stored textiles. What stood out was not only the incredible range of techniques, color combinations, and workmanship, but also a deep sense of the individual authorship and human artistry inherent to each piece. While tradition places an emphasis on repeated motifs, styles, and patterns for making — it is also a space in which the individual artist’s hand and touch comes through, as well as a bounded space in which to express new ideas by playing with the rules and systems of tradition.

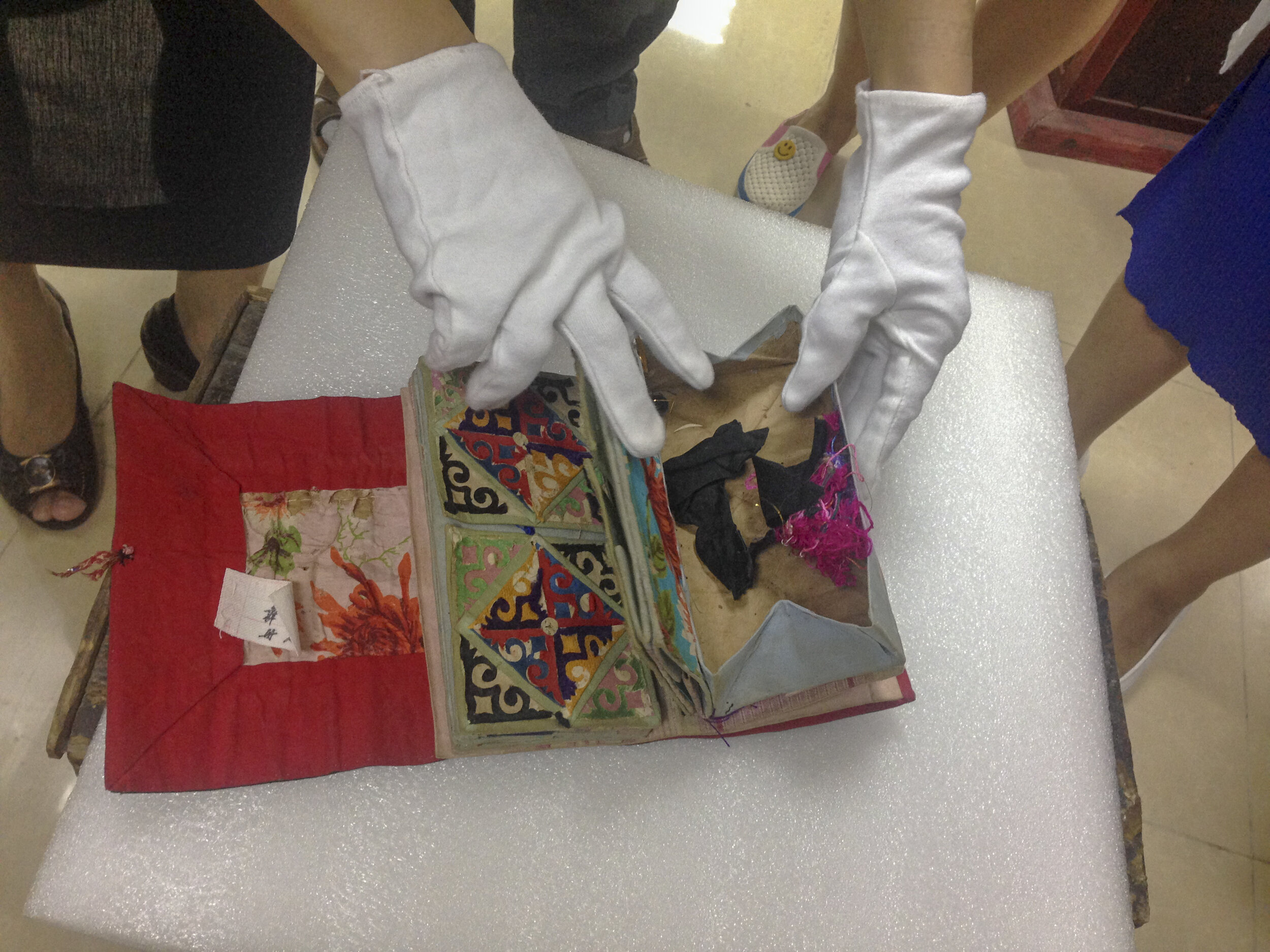

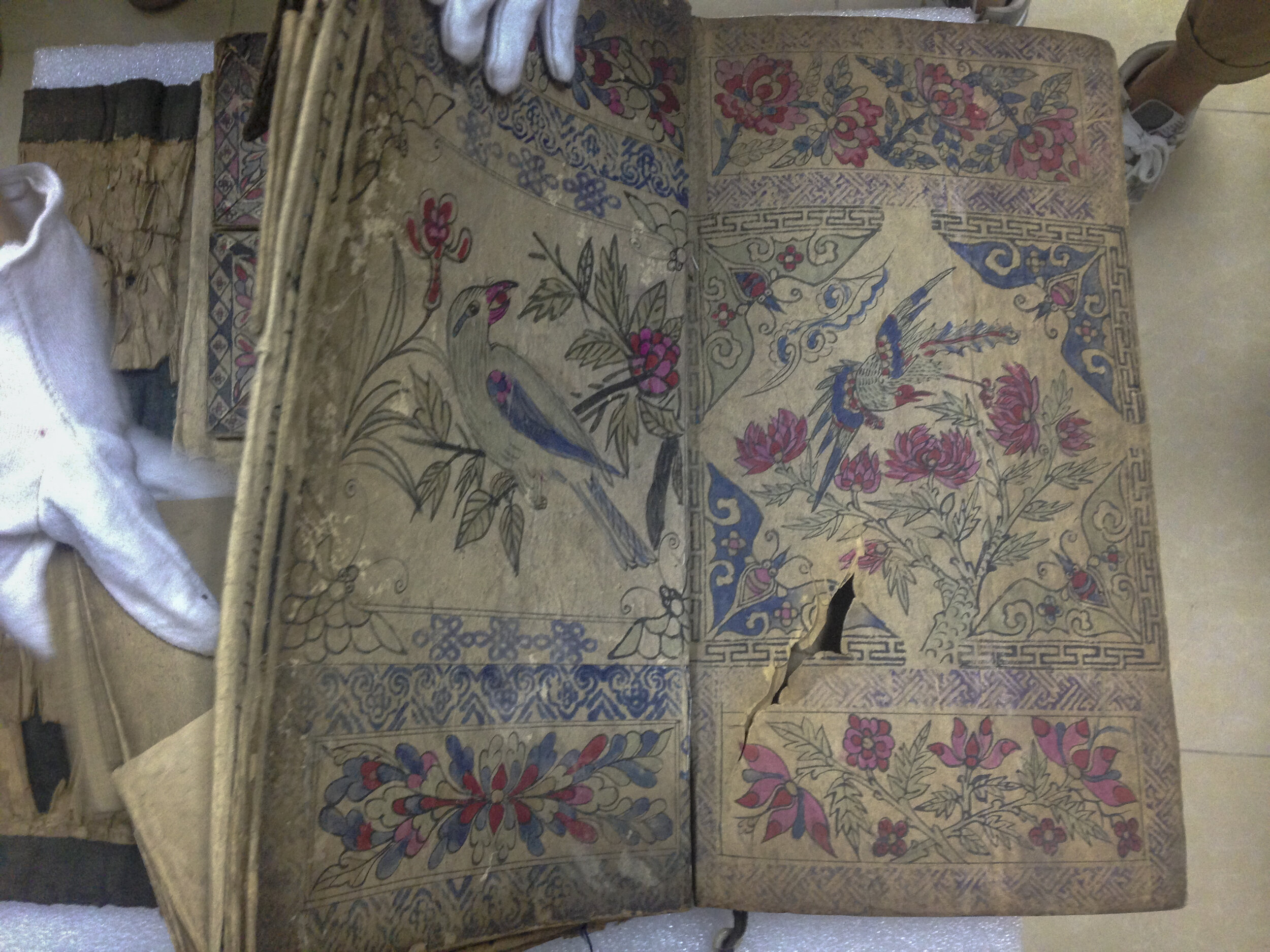

One of the most interesting objects shown in the exhibit were these sewing books. They are highly personal objects, crafted and decorated as carefully as the textiles themselves, and hold in their folded paper pockets, needles, thread, small tools, photographs, and other keepsakes.